It’s the special sorcery of serial fiction that it can make you look forward desperately to the very point at which there will nothing left of it. Having enjoyed successive cliffhangers, you’re happy to be taken just short of the last ledge, while the story leaps into history and you’re left with a lifetime memory.

In periodical fiction, there’s a lot a lot to be said for succeeding in finishing your story—we all have our fave TV dramas that were cancelled before their natural conclusion and comics suspended with years of tales left to tell.

So it was that 2012 offered more than its share of comic series with finales well worth there being literally nothing more to look forward to.

It helps to have material that never dies out because its substance circumnavigates the eternal. Writer Kieron Gillen (with rotating artists, most memorably Carmine di Giandomenico, Alan Davis and Stephanie Hans) knit the folkloric foundations of popular adventure with the contemporary storybook strains of comics in an unsurpassed way with the “Young Loki” series in Marvel’s Journey Into Mystery—a corny old title probably exhumed for copyright-protection purposes, but which marqueed one of the most clever and inventive series in the company’s history.

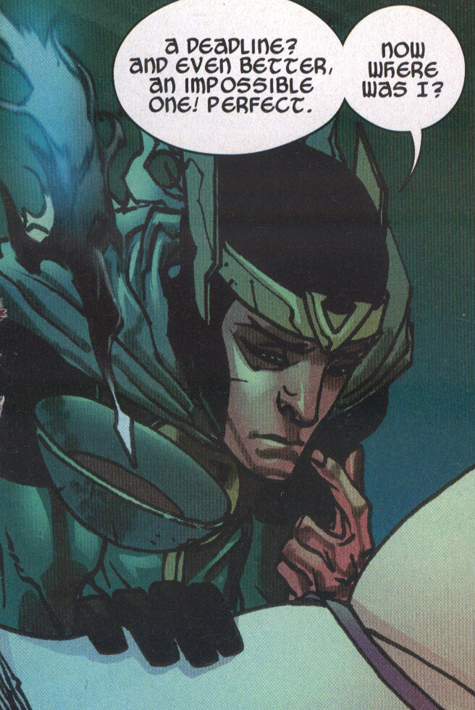

Concerning a God of Mischief reincarnated as a child (a witty, moralistic twist on the endless and consequence-free reboots of many pop properties), the series followed this subversive but good-hearted young god’s quest to do the right thing for the universe, as he sees it. He sees it, of course, through the warped lens of a calculating mind, and just as, in less multidimensional fiction (figuratively and literally), we’d worry about the triumph of the hero’s mission, in this one we watched for the survival of the protagonist’s heroism at all. Loki schemes several steps ahead of any healthier mind, factoring an eventual good with lots of asterisks, and in an era of agonizing global decisions this was an affecting parable of a personality willing to carry the consequences—like Judas as conceived by Borges, Loki doesn’t die for our sins, we live thanks to his; an edgy value to form a funnybook around.

The charm, humor, wonder and ingenuity of the book’s fairy tale voice and hallucinatory scenarios was like nothing in mainstream comics, and just like the Norse gods themselves it was destined to come to an end. But it reached a closure that’s as philosophically satisfying as any we can hope for; Young Loki plays cards with fate and can’t win forever, but his well-intentioned attempts and eventful, indelible run let us glimpse a short glorious season of who we might be.

As an apprentice in metaphysical arts, Loki is a kind of hard-boiled researcher, and it’s fitting that in an era of pop narrative that’s increasingly conscious of its own devices, some of the best stories would, on certain levels, be about story itself—and the heroes would be those for whom the word is mightier, and not just by one letter, than the sword.

The seeker-of-truth has always been a staple of popular fable; the wizard is the expert-witness of antiquity, and pop’s leading modern-day action-scholars are the Fantastic Four, a family of scientists and live-in support staff. It’s often said that superhero comics are “power fantasies,” and it’s long been said that “knowledge is power,” which is what makes the Fantastic Four franchise rather unique: it’s a knowledge fantasy.

In the hands of writer Jonathan Hickman for several miraculous years (the best with artists Steve Epting, Juan Bobillo, Nick Dragotta and di Giandomenico again), the series was illuminatingly self-referential, a saga in which future versions of the group’s resident children, Franklin and Valeria, as well as patriarch Reed Richard’s own time-traveling absentee father, return to try and rewrite a history they know will not turn out well. What might sound like a stock time-space thriller was exponentially more in Hickman’s hands—literally, for he had an imagination to grasp the infinite directions that time and narrative can go in, and an eye for the most fruitful and eventful paths. We all navigate possibilities, and changing our ongoing actions is a way of modifying the outcome of past events, which shift into something else depending on what our next moves make them have meant, if ya follow me. The Fantastic Four inhabit a workaday wonderverse in which such existential engineering is commonplace; quantum guardian angels who also epitomize the fractious and loving modern-day family.

That family was extended with a companion book, FF, standing for “Future Foundation,” a think-tank of exceptional children set up by Reed to map out viable futures with those who have the greatest stake in living them out. Most action franchises are designed to return readers to the point they started at so as to perpetuate what “worked” (that is, sold) before. The more adventurous ones turn the wheel in a way that draws in new elements which become essential to the canon. Hickman’s run brought you “back” to more of the same world than you ever imagined was there the first time, his mission and the time-travelling siblings’ a success. A parable of how the human family can survive anything it puts its mind to, the cycle showed that, like the expanding, redefining family unit itself, there are circles that can go on forever, but never have to close.

In an era of marriage equality, international adoptions and affinities of all occupational and social-media shapes, those family definitions are proliferating, and, in comics’ martial habitat, some are more nourishing than others. The Boys, created by Garth Ennis and Darick Robertson, almost met its end far short of the 72nd issue (or 90th counting related miniseries) that came out this year. Trapdoored by DC/WildStorm after a handful of issues, it found a home and acquired ever more followers at Dynamite Entertainment. Which was to comic history’s and pop erudition’s everlasting advantage, The Boys being one of the four most important and satisfying superhuman narratives of the century so far.

I use the term to distinguish from “superhero stories,” of which there are many that do their job and achieve artistic value. The superhuman narrative expands past costume conventions and reaches back to mythic precedents, with characters who are more in the realm of our recognition taking on problems magnified in scale but not scope from the ones we’re facing in fraying social orders and a transforming environment—the basic-black champions of The Matrix, the evolved strategic mind and physical modifications of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. The superhuman narrative also travels an axis clear of the moral conventions of “hero” and “villain,” giving us the dysfunctional social engineers of Gerard Way’s The Umbrella Academy, the conflicted mercenaries of Gail Simone’s Secret Six, and the exiled and embittered divinities of Peter David’s Fallen Angel, the other three important comics I mentioned.

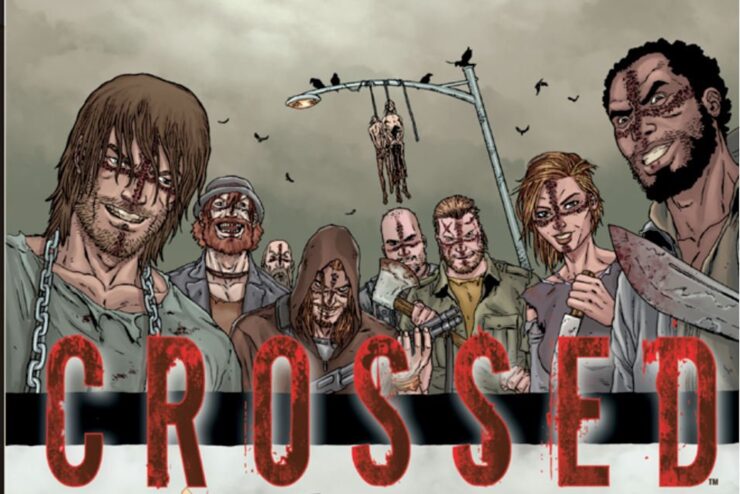

And The Boys—eerily anonymous trenchcoated enforcers for a secret government division that polices superbeings who are caricatures of the heroes we know from standard comics. In the world of this series, such superbeings are a commercial diversion, accidental heirs of a body-enhancing compound leaked in WWII by a corporation that wanted to corner the market in supersoldiers and privatize war. In the present day, the corporation manages the “supes” like real-world celebs, maintaining their identities for comicbook and merchandise tie-ins, neutralizing just enough of their public misbehavior, and grooming them for the occasional staged good deed. Also like entitled celebs and elites in our world, though, their deeds are very bad and the company has bigger things in mind for them, like reviving their original private-army purpose, and “The Boys” step in to covertly keep the fear of humankind in these false gods. The troupe is composed of men (and one woman) all damaged or bereaved in some way by the super-system, holding their grudge so that everyday people don’t have to find out what it’s like.

An incalculably violent, irresistibly hilarious and unflinchingly philosophical book, The Boys was Tarantino with more of a soul and even less of a filter; like Frank Miller’s Give Me Liberty, it was immensely ugly and entirely indispensable. And, at the last, shockingly beautiful—this was the kind of fantasy in which the series ends for many characters long before it does for us, and the sense of consequence was rare in a medium of perpetual franchises. Also by the traditional rules of comics, The Boys would be cast as the “supervillains,” but this book explored all that’s not at it seems, and its themes of corporatized warfare and cynical government were timed to an era of unidentifiable good guys (the time-period is about 2006-8, in a world where the 9/11 terrorists took out the Brooklyn Bridge but not the other buildings after a slightly smarter President had two planes shot down and the last one was let go by bungling stunt-fighting superheroes on a trial run, and we’re endlessly at war not with Afghanistan but Pakistan—a bad, sad dream of “what we’d do differently”).

But there was nothing ambiguous about the contrast in which Ennis (with Robertson and later artist Russ Braun) cast the morally logical path by showing the extremes of appetite and animosity; and at the end a vision, imperfect but appreciative, relieved but vigilant, emerged of what human monuments inevitably fall down and which human spirits unceasingly push up.

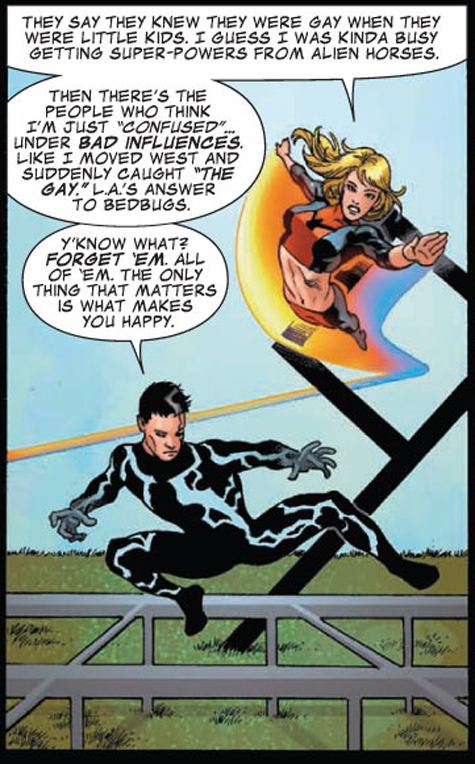

Just as The Boys took superhuman conventions into a world only as unbelievable as our own, one comic injected more of the feelings and concerns we recognize from real life into the superhero template than ever before. Avengers Academy concerned a kind of finishing school for young superheroes, an intriguing extension of the predecessor Avengers: Initiative book, which portrayed state-by-state government-approved teams of apprentice heroes, a kind of warning-labeled version of caped crusading. Both of these were a novel reflection on the rule of law in a genre often rooted in fantasias of vigilante justice.

Christos Gage wrote much of the Initiative run (taking it on from overworked and enough-brilliant Spider-Man head-scribe Dan Slott), and all of Academy, with a succession of artists (most notably co-founder Mike McKone, Sean Chen and Tom Grummett). Lots of comics get collected into “graphic novels” every few issues, but this one was that rare ongoing franchise that had true novelistic sweep and depth. From its start it was a kind of culmination, of the naturalism Stan Lee sought to bring to costumed characters and the sensitivity he wished to carry over from the romance comics that ruled the market before superheroes surged again in the early 1960s.

Melodrama is common in comics, in-costume or out, but no book has ever given these improbable characters credible and relatable emotional lives like Avengers Academy. The way the students wrestle with uncertain sexuality, abusive upbringings, autism variations, or just being well-adjusted in a world that’s not adjusted to them, while fighting off the most entertainingly crafted of cartoon menaces, was second to none. In a series clearly conceived as a one-line franchise-extruding concept, Gage and his collaborators achieved a comic book of ideas.

“Community” is a word taken in vain by many a marketer, but the extended family of the Avengers Academy went farther, into the dialogues in the backpage letter column, where more kids, and parents, and female readers of all ages than one is used to seeing take an interest in comics these days, had heated, and always respectful and considered, debates on the issues the comic touched on and the uncommonly attentive conception it had of growing up. Pulp tends toward utter escapism or cardboard issue-recitals; under Gage’s guidance Avengers Academy was an adventure reaching into everything we daydream while leaving out none of what we wonder about.

All great ensemble entertainments set their characters in a high-rise office, or a police precinct, or hospital, or barracks, and take us places that spark our imagination, while it scarcely matters where they’re set, because they place people we can recognize amidst dilemmas and decisions we’re all to used to facing. Avengers Academy’s everyday personalities just happened to go to work in other dimensions and cosmic wars. Like Tom DeFalco, Ron Frenz and Sal Buscema’s also improbably long-running, youth-oriented thinking-fan’s franchise Spider-Girl, this book wasn’t just a superhuman achievement, it was superhumane.

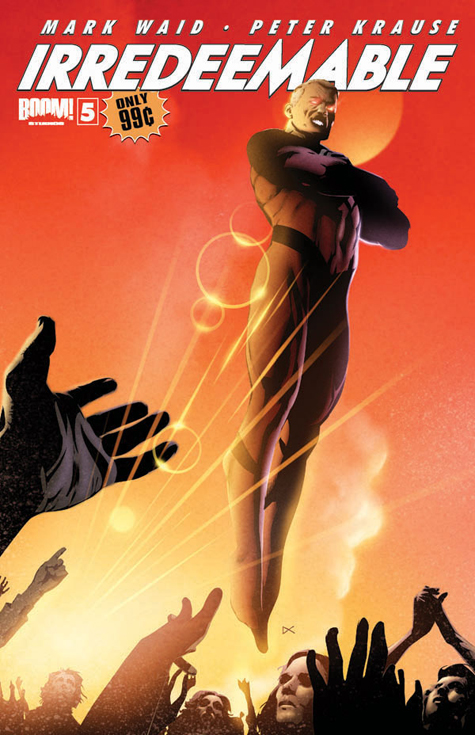

Grand designs can be beautiful ones too, and not every superstory needs to scale down to the level we’ve experienced to be profoundly about what makes us exist. Mark Waid’s Irredeemable and Incorruptible (done best with artists Diego Barretto and Marcio Takara, respectively) were meta-pulp meditations on the action pantheons raging through the multiplex firmament of the 2010s. The books concerned a Superman-like figure who goes rogue and starts laying waste to an Earth that depended on him but was perhaps incapable of appreciating him, while one of his archfoes steps up to fill the void. The superman, “Plutonian,” is unharnessed animus, the magnified embodiment of what a human does when he can (and this is a being who can do anything); the ex-villain, Max Damage, is calculating virtue, as fanatically straight-edge as he once was single-mindedly evil.

Echoes of local gangs being the only ones keeping order and feeding people after the government’s abdication during Katrina were clear in Max’s mission, as were the consequences of singular “superpowers” on our own world stage in the Plutonian’s rampage. Ever since Watchmen (or at least until Before Watchmen…if ya follow me), the superhero-comic-about-superhero-comics model has had a timer on it; people expect relatively brief runs and contained-novel closure. Irredeemable/Incorruptible lasted a total of 67 issues, and no one before Waid had attempted to take a tightly conceived statement like this and execute it in the long-form periodical nature of the pop it comments on.

In this way it added to that archive—these were the most unpredictably plotted, originally conceived comics in 70-plus years of superheroes, taking stock while taking the form’s building blocks in utterly new directions. The secret of what Plutonian really was, and how/if his misdeeds could be undone, and all the appalling, amazing innovations in sci-fi, time-travel, and psychodrama along the way, are best left to be discovered if you haven’t read the books; suffice it to say it took a writer of Waid’s classic command and titanic daring to see a way forward, and, in the face of monumental challenges for his characters and his chops, to see a way out.

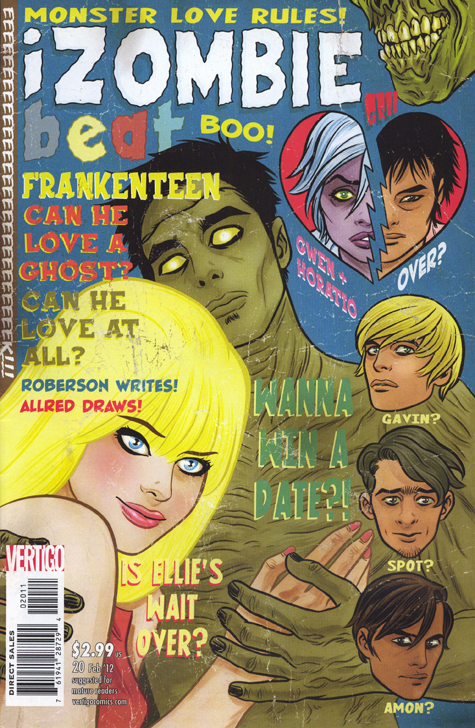

Somewhere between divine tragedy and earthbound farce was writer Chris Roberson and artist Michael Allred’s iZombie, a two-year diary of undead, vampiric and changeling twenty-somethings in the Pacific Northwest. An antidote to high-fashion teen-monster blockbusters and a metaphor for how misshapen we feel as we sort out our lives, iZombie had hipster charm to burn and endless good ideas combusting. Culminating in a Cthulhu-like attack epicentered in Oregon, the book drew together encyclopedias of mass occultism and bohemian chic in a concluding a-pop-calypse that cracked the cosmos while highlighting everyday feelings of community between our misfit true selves—like all the best monster fiction, swelling our humanity under pressures put on our mortal shells. I’m not sure the book came to a close when its creators wanted, but they fashioned a finale that was touchingly personal, and portrayed a passage from monstrous metamorphosis to saintly transformation that was religious in scope—a Holy-land ending, so to speak.

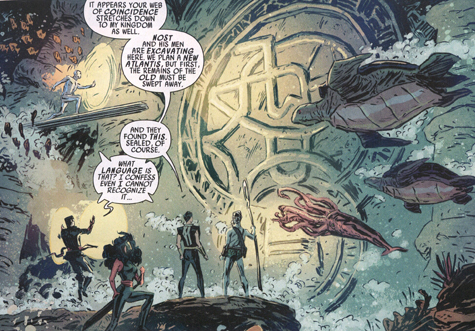

Also on a cosmic scale, Matt Fraction’s Defenders, the latest perennial reinvention of Marvel’s most eccentric franchise (with more of the company’s carousel of artists, most impressively Jamie McKelvie and Mitch & Bettie Breitweiser), was a type of summation of the entire Marvel cosmology. The run was limited (as Defenders reboots tend to be) to a single full year, but encompassed the very reasons for the “Marvel Universe”’s existence—not to mention the reasons why artists create and fans read comics.

First launched in the 1970s as a “non-team,” a kind of anti-Avengers composed of fractious misfits who could only come together on an ad-hoc world-crisis premise, Defenders was known as a haven for the more offbeat writers subverting the commonplaces of heroic fiction—definitively, the late Steve Gerber, who amped the book’s surreal satire to a legendary standard.

Fraction is one of Gerber’s natural heirs, though equally without precedent; the new book’s 12-issue ultimate trip hinged on worldwide unearthings of strange abstract key-like antennae, the “Concordance Engines,” which exert some mysterious influence on the plotlines of the universe. These devices serve as a kind of celestial stylus, around which Fraction wove astonishingly absurd and inventive dimensional setpieces on a quest to decode the source of the fictional world’s wonders themselves. If I’m describing it circularly that’s because I don’t want to give away too much, and because Fraction’s narrative formed a perfect loop (with plenty spirals on the way), tuning the clarity of how comics do what they do, and why we keep coming back.

Like many intelligent genre comics, its days were numbered, but its possibilities vast. The best endings are those which show the vital urgency of what’s next. So Happy Next-Year.

Adam McGovern’s dad taught comics to college classes and served as a project manager in the U.S. government’s UFO-investigating operation in the 1950s; the rest is made up. There is material proof, however, that Adam has written comicbooks for Image (The Next issue Project), Trip City.com, the acclaimed indie broadsheet POOD, and GG Studios, and blogs regularly at HiLoBrow.com, ComicCritique and his own recently-launched emotional outlet Fanchild. He lectures on pop culture in forums like The NY Comics & Picture-story Symposium and interviewed time-traveling author Glen Gold at the back of his novel Sunnyside (and at this link). Adam proofreads graphic novels for First Second, has official dabblings in produced plays, recorded songs and published poetry, and is available for commitment ceremonies and intergalactic resistance movements. His future self will be back to correct egregious typos and word substitutions in this bio any minute now. And then he’ll kill Hitler, he promises.